MICHAEL SLATER: Well, that's a reference to the Reverend Malthus. ROMER: Dickens biographer Michael Slater says that last phrase, surplus population - that is the key to understanding the fight Dickens is picking with economics. HANNAH BLOOMQUIST: (As character) And they'd rather die first.ĪDAM: (As Ebenezer Scrooge) If they would rather die, then they'd better do so at once and decrease the surplus population. Those that are badly off must go there.ĪLEXIS BROWN: (As character) But so many cannot go there. ROMER: I recently visited Branford High School in Branford, Conn., to watch its staged adaptation of "A Christmas Carol." It turns out, even if your Ebenezer Scrooge is a teenager, asking for donations to Christmas charities still a bit of a nonstarter.ĪDAM JACKSON: (As Ebenezer Scrooge) My taxes go to support the prisons and the workhouses. The story is deeply preoccupied with questions of wealth and poverty and with a then-brand-new social science that purported to be able to answer those questions - political economy, economics. KEITH ROMER, BYLINE: "A Christmas Carol" takes place during the Industrial Revolution. Keith Romer, with our Planet Money podcast, says this holiday classic is a pointed critique of what was then a pretty new social science called economics.

But Dickens also had another lesson in mind when the story was published in 1843. It's a heartwarming reminder of the importance of generosity.

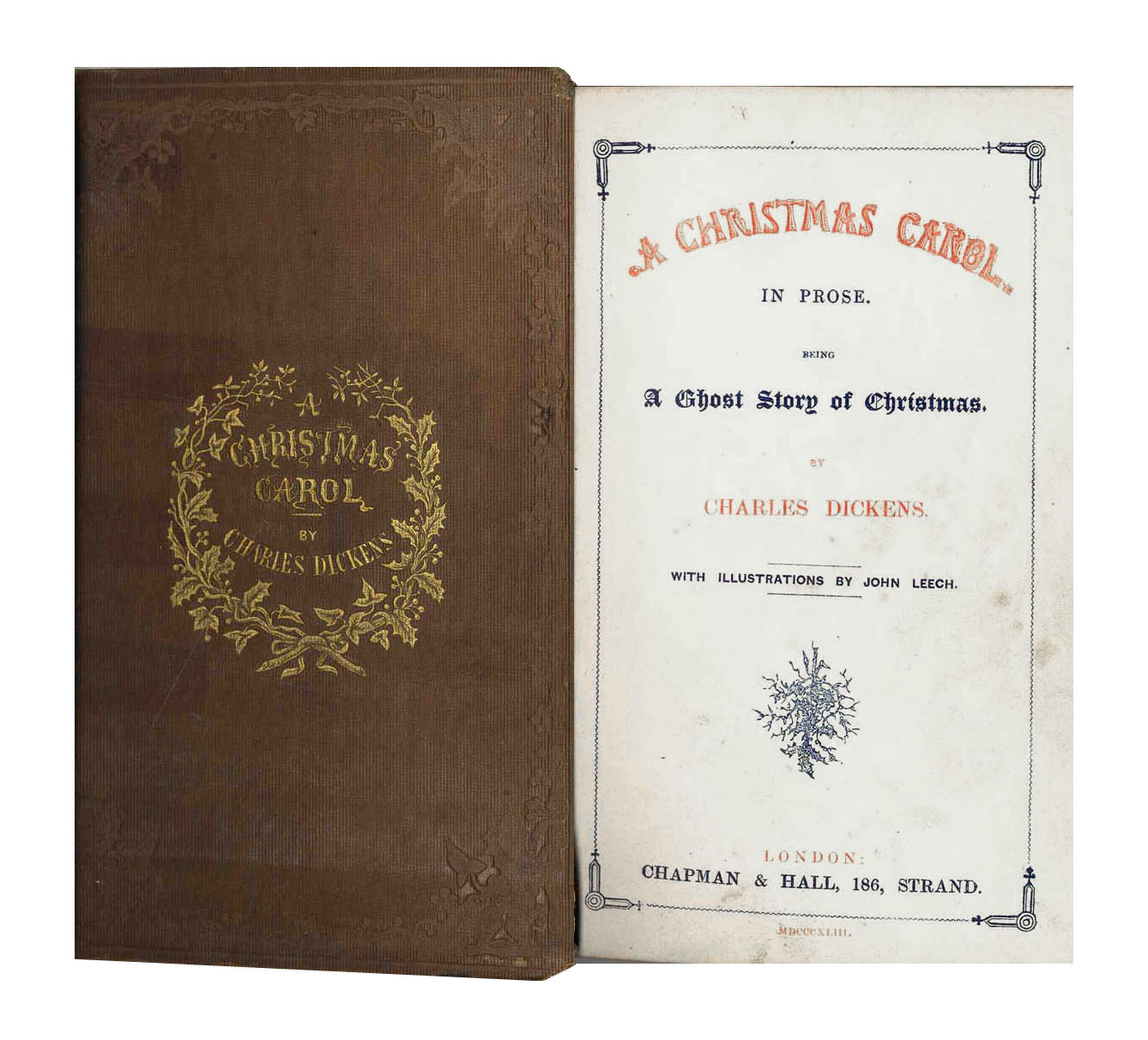

Of course, it tells a story of three Christmas spirits who teach the miser Ebenezer Scrooge the true meaning of the holiday. "A Christmas Carol" by Charles Dickens is a redemption story.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)